Spice Route

Myths &

Misconceptions

Spice Timeline

Early European

Pepper Imports

Prices & Wages

World/US spice

consumption

Myth no. 1:

Spices were used by medieval Europeans to mask putrid and spoiled foods.

Let’s face it, the people who could afford spices were precisely the ones who could throw out the rotten venison haunch. The manuals are replete with instructions on cooking meat soon after the animal is slaughtered. If the meat was hung up to age, it was for no more than a day or two, but even this depended on the season. Not that bad meat did not exist. From the specific punishments that were prescribed for unscrupulous traders, it is clear that rotten meat did make it into the kitchens of the rich and famous, but then it also does today. The advice given by cookbook author Bartolomeo Sacchi in 1480 was the same as you would give now: throw it out.

Myth no. 2:

Spices were used my premodern people because they had unrefined, barbaric tastes.

This is the subtext of much 20th century French writing on the subject. Anyone who doesn’t use spices the way the modern French do (i.e. not at all) must be a barbarian. Tell that to the Indians, Moroccans, Vietnamese and others who use way more spice than any medieval European did! Some cultures happen to like the way spicy food tastes and think that mold-covered putrefied milk (i.e. Camembert) is vile. I happen to like both.

Myth no. 3:

Spices were used to preserve food.

Not only is this an affront on common sense, it completely contradicts what’s written in the old cookbooks. Throughout human history, until the advent of refrigeration, food has been successfully preserved by one of three ways: drying, salting, and preserving in acid. Think prunes, prosciutto, and pickles. The technology of preserving food wasn’t so different in the days of Charlemagne, the Medici, or even during the truncated lifetime of Marie Antoinette, even though the cooking was entirely different in each era. What’s more old cookbooks make it clear that spices weren’t used as a preservative. They typically suggest adding spices toward the end of the cooking process where they could have no preservative effect whatsoever. In at least one renaissance Italian cookbook the author suggests that pepper might even hasten spoilage!

Myth no. 4:

Spices used to be worth their weight in gold.

Pricey perhaps but nowhere near their weight in gold. In Venice, in the early fifteenth century, when pepper hit an all-time high, you could still buy more than three hundred pounds of it for a pound of gold. And while it’s true that a pound of ginger could have bought you a sheep in medieval England, that may tell you more about the price of sheep than the value of spice. Sheep in those days were small, scrawny, plentiful, and, accordingly, cheap. You will also read that pepper was used to pay soldiers’ wages and even to pay rent. But once again, this requires a little context. Medieval Europe was desperately short of precious metals to use as currency, and if you needed to pay a relatively small amount (soldiers didn’t get paid so well in those days), there often weren’t enough small coins to go around. Thus, pepper might be used in lieu of small change. But sacks of common salt were used even more routinely as a kind of currency in the marketplace. Cloves and nutmeg were perhaps two or three times the price of pepper and ginger depending on the time and place but that still made them affordable to the more than just the royals.

The origin of this particular myth may originate with Martin Behaim’s 1492 globe. One of the annotations, no doubt hyperbolic, notes that "One must know that the spices from the islands in East India must pass through many hands before they come here to our land....No wonder spices for us cost their weight in gold.”

Myth no. 5:

Food was seasoned with enormous quantities of spice in the Middle Ages.

Well perhaps enormous if you are a French historian born in 1900s. Fernand Braudel once referred to the medieval fashion for spiced food as an “orgy of spice.” More likely the very wealthy in medieval and renaissance Europe used about as much spice as an average Moroccan does today. And perhaps a third or less of the typical Indian dish. Hardly an orgy.

Myth no. 6:

Cooks stopped using spices in cooking after the 1600s.

The drop off in spice use was certainly much more gradual than this, at least outside of France. You find lots of recipes in most non-French sources throughout 1700s and even 1800s that harken back to the middle ages in the way they use spice. What probably did occur after about 1700 though is the well-spiced meat and fish dishes became less and less trendy.

c. 1700 BCE — Estimated date of cloves found in an archaeological

dig in Syria.

1224 BCE — Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II embalmed with peppercorns up

his nose.

c. 1000 BCE — Queen of Sheeba visits King Solomon bearing spices as a

house gift (?).

476 — Rome falls to the Barbarians.

550 — Byzantine merchants reported in Ceylon buying spice.

946 — Poisoned pepper sauce reported on the table of King Louis IV

of France.

1095 — First Crusade proclaimed by Pope Urban II to “liberate”

Jerusalem from Muslim rule.

1204 — sack of the Christian Orthodox city of Constantinople by

Venetian and Frankish troops in the course of the

Fourth Crusade.

1298 — Marco Polo claims that for every Italian spice galley in

Alexandria, a hundred dock at the Chinese port of Zaiton

(Quanzhou).

1348 — The Black Death sweeps Europe following the same routes

as the spice trade.

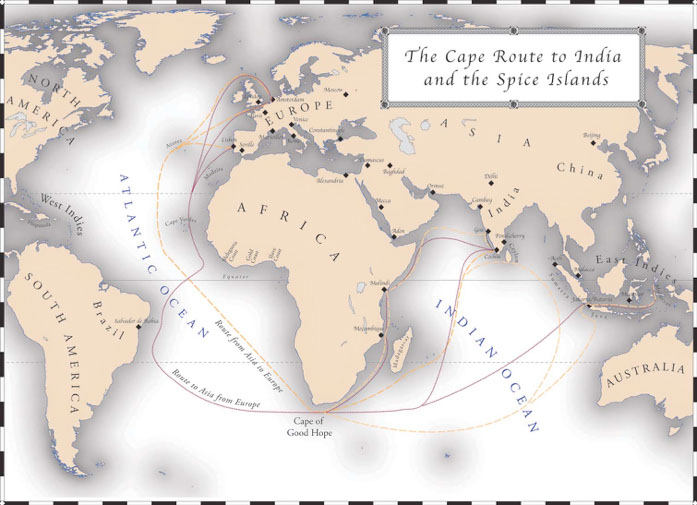

1488 — Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias rounds the Cape

of Good Hope.

1492 — Genoese mariner Cristoforo Colombo (Christopher Columbus),

financed by the Castilian queen Isabel, reaches the Caribbean,

insists that he has arrived in the East Indies. He does find chilies

though noting “The pepper which the local Indians used as a spice

is more abundant and more valuable than either black or

melegueta pepper.”.

late 1490s — Chilies introduced into Europe by Spanish.

1498 — Vasco da Gama arrives in Calicut, trades in his silverware

for spices—see map.

1500 — Portuguese fleet led by Cabral “discovers” Brazil. Returns

to Lisbon (1501) with a paltry 2000 quintals (roughly

120,000 kg) of spice.

1501 — Venetian spice trader Girolamo Priuli writes in his journal:

“[to Venice, the loss of the spice trade] would be like the loss

of milk and nourishment to an infant.”

1503 — Returning from his second trip, Vasco da Gama

and his men arrive in Lisbon with some 26,000

quintals of pepper and 6-7,000 quintals of other

spices, chiefly cinnamon (about 1,800,000 kg in all).

1510 — Goa seized by the Portuguese.

early 1500s — Chilies introduced into India by Portuguese.

1511 — Portuguese Captain António de Abreu, leads the

first European expedition to reach the Banda

Islands, home to nutmeg and mace.

1568 — Spain invades the Netherlands, beginning of

“Eighty Years War.”

1580 — Portugal is absorbed into the Spanish Empire.

1597 — First Dutch expedition returns to Holland after

having reached Bantam in what is now Indonesia.

1600 — English East India Company chartered by Queen

Elizabeth I.

1602 — Dutch East India Company (VOC) chartered.

1609 — Island of Neira (in the Banda archipelago) is

seized by the Dutch East India Company and the

Dutch government“ to be kept by us forever,”

making it the Netherlands’ first official East

Indian colony.

1618 — Thirty Years War begins in Central Europe.

1619 — Founding of Batavia in Java as headquarters of

the Dutch East Indies.

1621 — The inhabitants of the nutmeg producing Banda islands are

massacred by the troops of the Dutch East India Company (VOC)

under the leadership of Jan Pieterszoon Coen.

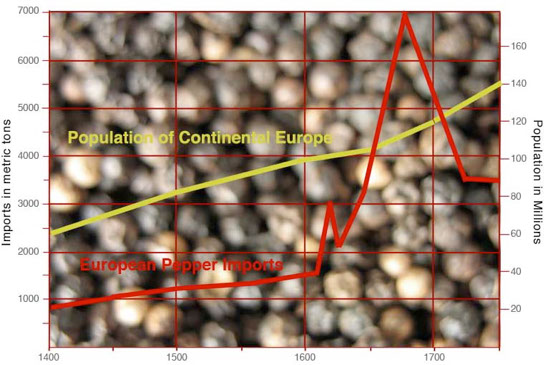

c. 1670 — European pepper imports reach 7,000,000 kg, the

highest they would be until the 19th century.

Following the 1670s imports fall by almost half .

1625 — The Dutch destroy some sixty-five thousand clove

trees in Ceram’s Hoamoal Peninsula (today’s Indonesia)

to maintain their monopoly.

1640 — Portugal regains independence from Spain.

1648 — End Thirty Years War.

1656 — Ceylon (Sri Lanka) is conquered by Dutch.

c. 1750 — Pierre Poivre steals nutmeg and clove seedlings from

Dutch Indonesia and plants them on the French Indian Ocean

colonies of Mauritius and Réunion.

1795 — Jonathan Carnes sails from Salem, Massachusetts for the East

Indies, bringing Americans into the spice trade. Connecticut

comes to be known as the “nutmeg” state, though it is unclear

whether this is due to her sailors taking part in the spice trade

or to the reputation of it’s woodworkers in fashioning counterfeit

nutmegs out of wood

1799 — Dutch East India Company disbanded.

1803-15 — Napoleonic wars.

1843 — The Caribbean British colony of Granada starts

producing nutmeg—today it is one of the world’s premier

producers.

1939-45 — World War II.

1950 — Indonesia (formerly the Dutch East Indies) gains

independence.

1961 — Portugal’s last Indian colony, Goa, is annexed by

India.

The data for pepper imports up to about 1650 is taken from a chart in C.H.H. Wake, “The Portuguese factory and trade in pepper in Malabar during the 16th century” in Spices in the Indian ocean World (Aldershot, UK; Brookfield, VT: Variorum, c. 1996), p. 173 and the later figures from Kristof Glamman, Dutch-Asiatic Trade: 1620-1740 (Copenhagen: Nijhoff, 1958), p. 74. Population figures are from Atlas of World Population History (New York: Facts on File, 1978), p.18.

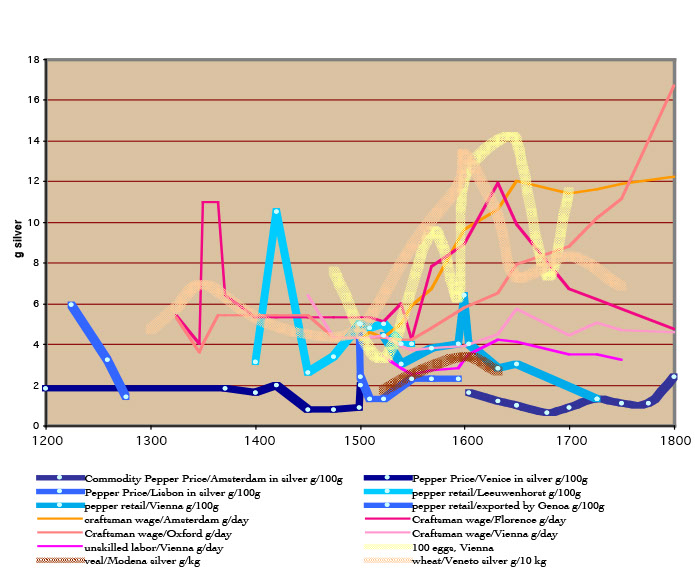

Prices and Wages in Europe 1200-1800

There is an ongoing assumption among historians that (a) spices kept getting cheaper over time and (b) that they became more affordable as time went on. Both are vast simplifications as I hope this chart points out wholesale pepper prices remained surprisingly steady over the centuries--see the dark blue lines. There was a modest dip in the second half of the 15th century, a modest rise as the Portuguese took over and then a gentle slide in price as the Dutch entered the market after 1600. Admittedly, retail prices (at least in the Netherlands and Austria) fluctuated much more wildly--see the light blue lines. It’s worth noting the pepper gets relatively cheaper with regards to wheat and eggs in the sixteenth century and though wages also rise in most places the skyrocketing cost of the basics may have made the amount of disposable income available for spices disappear altogether. Pepper wasn’t exactly cheap but then it wasn’t so expensive as some have claimed. A worker could, on average buy anywhere from 200g (7 oz) to 500g (17 oz) of pepper for a day’s wage, an enormous amount if you’re cooking with it!

Keep in mind that the data before 1350 is highly speculative but the rest is fairly reliable, especially after 1400. The price and wage data are mostly gleaned from the Global Price and Income History Group and Datafiles of Historical Prices and Wages. Extensive price data on spices in Amsterdam can be found in database compiled by Posthumus. The early data on Genoa comes from a couple of merchants accounts and may or may not be reliable. (the numbers are from Jehel, Georges.

Les Génois en Mediterranée occidentale: fin XIème - début XIVème siècle: ebauche d'une stratégie pour un empire [Amiens: Centre d'histoire des sociétés, Université de Picardie, 1993])

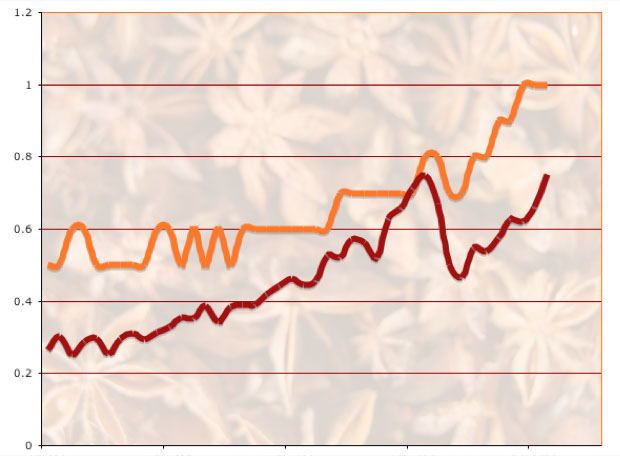

World & United States

Per Capita Spice Consumption

1961-2002 (kg/capita)

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

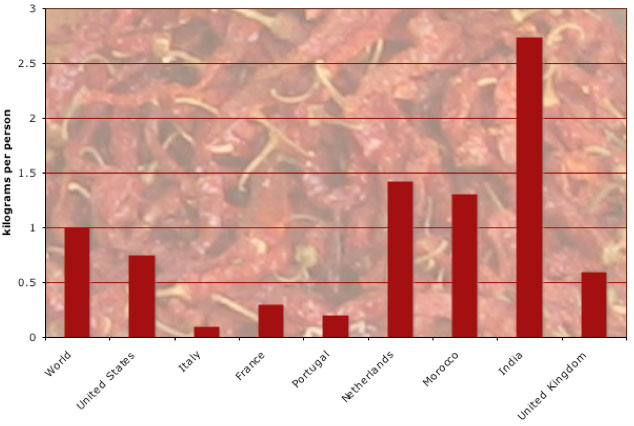

Spice Consumption

in Selected Countries (2002)

Source for both graphs: Faostat