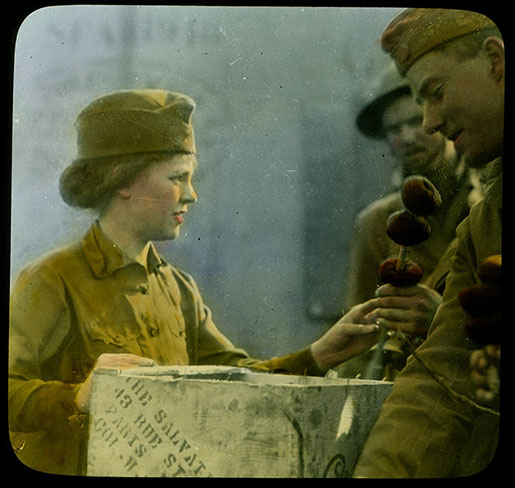

Donut Lassies

The story of how the fried dough circles took on such a pivotal role in the Salvation Army’s mission on the Western Front has the ring of the miracle of the loaves and fishes. When the United States joined the war to end all wars in 1917, the Salvation Army and other charities followed the doughboys into the muddy fields of northern France. (Incidentally, the term “doughboys” dates to the Mexican-American War of 1846–48 and has nothing to do with donuts.) Before shipping overseas, the Salvation Army’s female volunteers were steeled for the ordeal by their superiors. There was the danger of the shells, of course, but there was a more pressing threat to the young women’s virtue. Commander Evangeline Booth directed the young women to “put away the arts and coquetries of youth,” a daunting task given that they would soon be wading into fields of testosterone-fueled postadolescents.

The story of how the fried dough circles took on such a pivotal role in the Salvation Army’s mission on the Western Front has the ring of the miracle of the loaves and fishes. When the United States joined the war to end all wars in 1917, the Salvation Army and other charities followed the doughboys into the muddy fields of northern France. (Incidentally, the term “doughboys” dates to the Mexican-American War of 1846–48 and has nothing to do with donuts.) Before shipping overseas, the Salvation Army’s female volunteers were steeled for the ordeal by their superiors. There was the danger of the shells, of course, but there was a more pressing threat to the young women’s virtue. Commander Evangeline Booth directed the young women to “put away the arts and coquetries of youth,” a daunting task given that they would soon be wading into fields of testosterone-fueled postadolescents.

One of the earliest Salvation Army outposts was some 150 miles east of Paris and 20 miles behind the front in the village of Montiers-sur-Saulx. The New York office had arranged two circus tents to be sent over to serve as the army’s HQ. Back home, the Salvation Army was known for its street theater, marching bands, and popular hymns. Soon enough they were organizing much the same in French village squares, where they found a ready audience among the uniformed men, who were none too eager to meet their maker. While this sort of pious entertainment was better than nothing, it couldn’t make up for the shells or the pestilential weather. As Evangeline Booth tells it in her poetically augmented annals of war, “It had been raining steadily for thirty-six days, making swamps and pools everywhere. Depression like a great heavy blanket hung over the whole area.” Then heavenly inspiration struck.

The way the diaries of Ensign Margaret Sheldon tell it is a little more prosaic: she and her comrade Adjutant Helen Purviance had gotten the notion that donuts would make a nice change from the pies, cocoa, and fudge they’d been making for the boys. So, in late September 1917, they got ahold of the ingredients for a batch of dough. According to army records, the honor of frying the first donut fell to Purviance. It turned out to be the first of many. Soon enough, all the lassies, as the women came to be called, were making donuts by the thousands. The women improvised as they could, rolling out the donuts with a grape juice bottle, cutting them out with a baking powder can, and poking out the holes with a funnel. They sold the fried rings at cost (and often on credit) for about twenty cents a half dozen. As the Christmas of 1917 approached, Sheldon jotted down in her diary, “I made fifty-six pies and 1,500 d’nuts and they went fine. Then on Sat. I made fifty pies and 2,000 d’nuts.” The ensign estimated that she cooked more than a million donuts before the war was out.

As the conflict dragged on, the Salvation Army’s pie and donut dispensaries multiplied, and their contribution to American morale grew ever more critical. Despite the war shortages, the American high command made sure the flour and lard for the donuts got through, even if they sometimes needed a little reminder. There was usually the will and even the money, but there weren’t always supplies. Certainly the local market was no use. The French were surviving on black bread made of barley flour and other donut-unfriendly ingredients. The only place to get the necessary sugar, flour, and lard was through the US Army commissary. Luckily, the lassies hadn’t entirely put away their arts and coquetries; they knew that the way to a man’s heart—even if he happened to be wearing a general’s uniform—was through his stomach.

Running low on supplies, a Salvation Army adjutant decided to go to the source. The lassies supplied him with a dozen apple pies, twelve hundred freshly baked donuts, and one big gorgeous chocolate cake, which he packed into a rough army truck that he drove to the local American Expeditionary Force headquarters. The general was thoroughly pleased with his cake, as were all the officers whose palms were greased with the oily pastries, so pleased in fact, that as the adjutant was leaving, he discovered seven tons of flour, sugar, and lard being loaded into his rusty vehicle.

The Salvation Army had long had unorthodox ways of getting things done, something that hadn’t always endeared it to the American mainstream. This changed dramatically during the war. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (the former president’s son) spoke for many when he wrote of his service in France, “Before the war I felt that the Salvation Army was composed of a well-meaning lot of cranks. Now what help I can give them is theirs. My feelings are well illustrated by a conversation I overheard between two soldiers. One said, ‘Say, Bill, before this war I used to think it good fun to kid the Salvation Army. Now I’ll bust any feller on the bean with a brick if I see him botherin’ them.’” Donuts had a lot to do with it. “The American soldiers take their hats off to the Salvation Army,” wrote a correspondent for the New York Times in 1918, “and when the memoirs of this war come to be written the doughnuts and apple pies of the Salvation Army are going to take their place in history.”

Today, it’s hard to fully appreciate the importance of the Salvation Army’s presence in the trenches, in part because government has taken over many of the roles charitable and/or religious organizations used to take on. Today, it’s army psychologists who deal with morale, and if the US army were looking to provide donuts to the troops, they would likely turn to a slick military contractor--which would no doubt charge the American taxpayer twenty-four-karat prices for the glazed rings.

The lassies had no need of any of that; they had God and a dress code that almost guaranteed the soldiers wouldn’t violate the young women’s sacred donut mission. If you stop to think about it, the holey objects of desire were as loaded with symbolism as they were with hog fat. Anthropologists have long recognized the perforated circle as a symbol of fertility and feminine sexuality—the female analog of the phallus. In some cases, this is explicit, such as in the ring-shaped, plaited, and egg-encrusted cakes traditional for Easter throughout the Mediterranean, but it’s true of other holey pastries as well. And it’s not just tenured academics who hold this opinion; just look under donut in any dictionary of slang. I’m not the only one who sees something distinctly suggestive about young women distributing circle-shaped snacks to men clutching their well-oiled, bayonet-tipped rifles.

Needless to say, this is not a reading Commander Booth would have condoned. She tells the story of a young adjutant (presumably Helen Purviance) who gave the donuts a much more maternal spin: “[I]nvariably the boys would begin to talk about home and mother while they were eating the doughnuts. Through the hole in the doughnut they seemed to see the mother’s face, and as the doughnut disappeared it grew bigger and clearer.” For the purposes of their sanity, it was probably easier for the soldiers to think of the young women as mother or at least sister figures rather than the alternative. That was certainly the way the Salvation Army’s Colonel William Barker explained it to a reporter from the Boston Daily Globe:

[The donuts] put pep into every doughboy. Every doughboy felt his mother was somewhere just back of the lines in the midnight mists and damps—frying doughnuts for him just as she used to do, and the Germans noticed the improved morale of the Yankees.

The round, jolly-faced, homely apple pie and the laughing, golden brown doughnuts shouldered the rifles and fought like—well the Spirit of ’76 at Chateau Thierry and St. Mihiel [two prominent World War I battles].

It’s easy to forget that the lassies weren’t in France merely to provide a morale booster. Many of them genuinely believed they were on a spiritual or religious quest. The donuts weren’t just a sideline, they were part and parcel of the mission. As an editorial in an early edition of the War Cry, the Salvationist newspaper, explained, “The genius of the Army has been…that it has religionized secular things…it has brought religion out of the clouds into everyday life, and has taught the world that we may and ought to be as religious about our eatings and drinkings and dressing as we are about our prayings.” In much the way that the army had earlier converted tavern songs into hymns, during the war, the lassies transubstantiated donuts into a kind of spiritual host. In the way they saw it, the coffee and donuts they handed out weren’t so different from the eatings and drinkings of a Christian mass.

Despite the fact that no more than about 250 Salvationists actually served in France, the lassies with their donuts became the organization’s calling card.